Julian Jaynes' The Origin Of Consciousness In The Breakdown Of The Bicameral Mind is a brilliant book, with only two minor flaws. First, that it purports to explains the origin of consciousness. And second, that it posits a breakdown of the bicameral mind. I think it's possible to route around these flaws while keeping the thesis otherwise intact. So I'm going to start by reviewing a slightly different book, the one Jaynes should have written.

Theory of mind, how people think of the thought of older cultures, how people translate old works.

a typical translation might use a phrase like “Fear filled Agamemnon's mind”. Wrong! There is no word for “mind” in the Iliad, except maybe in the very newest interpolations. The words are things like kardia, noos, phrenes, and thumos, which Jaynes translates as heart, vision/perception, belly, and sympathetic nervous system, respectively. He might translate the sentence about Agamemnon to say something like “Quivering rose in Agamemnon's belly”. It still means the same thing - Agamemnon is afraid - but it's how you would talk about it if you didn't have an idea of “the mind” as the place where mental things happened - you would just notice your belly was quivering more. Later, when the Greeks got theory of mind, they repurposed all these terms.

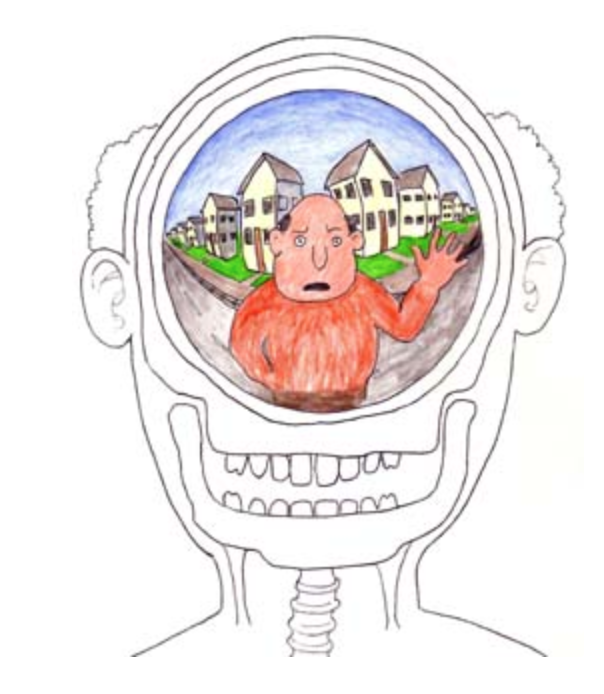

Suppose Achilles is overcome with rage and wants to kill Agamemnon. But this would be a terrible [idea]; after [thinking] about it for a while, he [decides] against. If Achilles has no concept of any of the bracketed words, nothing even slightly corresponding to those terms, how does he conceptualize his own actions? Jaynes:

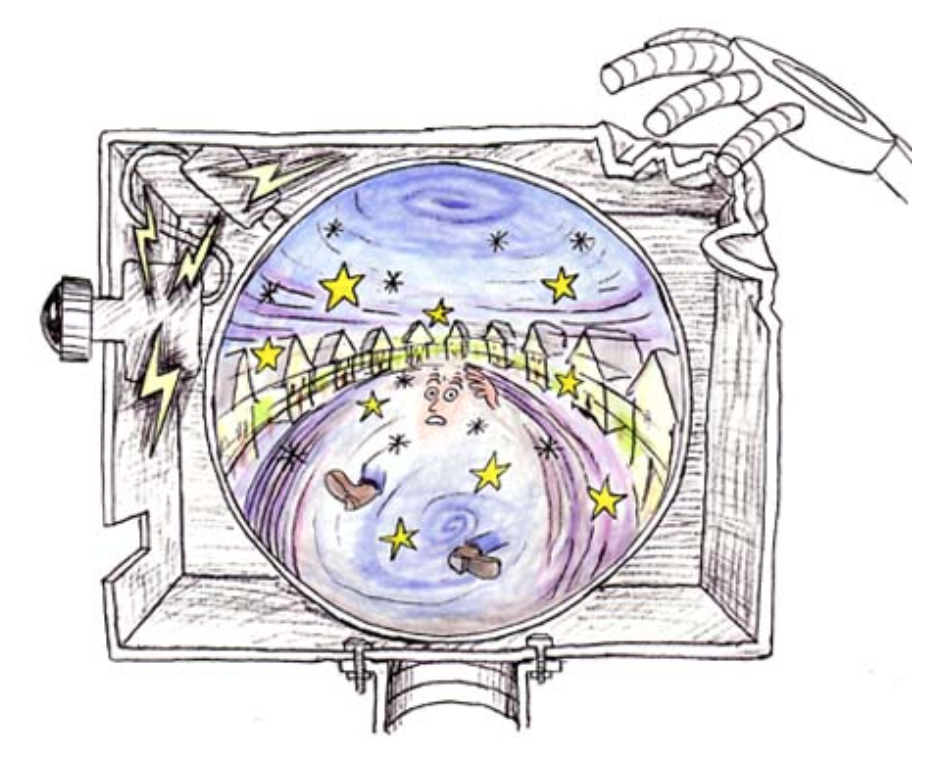

The response of Achilles begins in his etor, or what I suggest is a cramp in his guts, where he is in conflict, or put into two parts (mermerizo) whether to obey his thumos, the immediate internal sensations of anger, and kill the king, or not. It is only after this vacillating interval of increasing belly sensations and surges of blood, as Achilles is drawing his mighty sword, that the stress has become sufficient to hallucinate the dreadfully gleaming goddess Athene who then takes over control of the action and tells Achilles what to do.

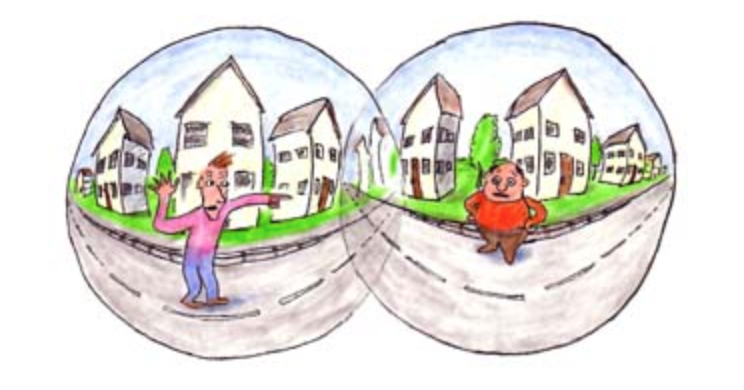

As you go about your day, you hear a voice that tells you what to do, praises you for your successes, criticizes you for your failures, and tells you what decisions to make in difficult situations. Modern theory-of-mind tells you that this is your own voice, thinking thoughts. It says this so consistently and convincingly that we never stop to question whether it might be anything else.

If you don't have theory of mind, what do you do with it?

Then, around 1250 BC, this well-oiled system started to break down. Jaynes blames trade. Traders were always going into other countries, with different gods. These new countries would be confusing, and the traders' hallucinatory voices wouldn't always know all the answers. And then they would have to negotiate with rival merchants! Here theory of mind becomes a huge advantage - you need to be able to model what your rival is thinking in order to get the best deal from him. And your rival also wants theory of mind, so he can figure out how to deceive you. Around 1250 BC, trade started picking up, and these considerations became a much bigger deal. Then around 1200 BC, the Bronze Age collapsed.

But as theory of mind spread, the voices of the gods faded. They receded from constant companions, to only appearing in times of stress (the most important decisions) to never appearing at all. Jaynes interprets basically everything that happened between about 1000 BC and 700 BC as increasingly frantic attempts to bring the gods back or deal with a godless world.

Now, to be fair, he cites approximately one zillion pieces of literature from this age with the theme “the gods have forsaken us” and “what the hell just happened, why aren't there gods anymore?” As usual, everyone else wimps out and interprets these metaphorically - claiming that this was just a poetic way for the Mesopotamians to express how unlucky they felt during this chaotic time. Jaynes does not think this was a metaphor - for one thing, people have been unlucky forever, but the 1000 - 750 BC period was a kind of macabre golden age for “the gods have forsaken us” literature.

So people got desperate. He says this period was the origin of augury and divination. Omens “were probably present in a trivial way” before this period, but not very important; “there are, for example, no Sumerian omen texts whatsoever”. But after about 1000 BC, omens become an international obsession. [...] And then there are the demons. Early Sumerians didn't really worry about demons. Their religion was very clear that the gods were in charge and demons were impotent. Post 1000 BC, all of this changes. [...] and angels, and prophets, and all the other trappings of religion. When the gods spoke to you every day, and you couldn't get rid of them even if you wanted to, angels - a sort of intermediary with the gods - were unnecessary. There was no place for prophets - when everyone is a prophet, nobody is. There wasn't even prayer, at least not in a mystical sense - as Jaynes puts it, “schizophrenics do not beg to hear their voices - it is unnecessary - in the few case where this does happen, it is during recovery when the voices are no longer heard with the same frequency.”

The Assyrians invented the idea of Heaven. Previously, Heaven had been unnecessary. You could go visit your god in the local ziggurat, talk to him, ask him for advice. But word went around that gods had retreated to heaven - some of the stories even use those exact words, blaming the Great Flood or some other cataclysm. The ziggurats shifted from houses for the gods to e-temen-an-ki - pedestals that the gods could descend to from Heaven, should they ever wish to return.

By 500 BC, the ability to hear the gods was limited to a few prophets, oracles, and poets. Jaynes is especially interested in this last group - he cites various ancient sources claiming that the poets only transcribe what they hear gods and goddesses sing to them (everyone else wimps out and says this is metaphorical).

Jaynes ends by referencing one of my favorite ancient texts, Plutarch's On The Failure Of Oracles. Plutarch, writing around 100 AD, is not a skeptic. He believes oracles work in theory. But he records a general consensus that they don't work as well as they used to, and that some day soon they will stop working at all.

The last oracle to fade away was the greatest - Delphi, perched atop a fantastic gorge as if suspended between Heaven and Earth. Jaynes tries to give us an impression of how important it was in its time; important people from all over the classical world would make the pilgrimage there, leave lavish gifts, and ask Apollo for advice on weighty matters. He thinks that the oracle's fame protected it; if a cultural validation is an important ingredient in god-hearing, Delphi had the strongest and best. Its reputation was unimpeachable. Still, in the centuries after Plutarch, its prophecies became rarer and rarer; the Pythia's few divine utterances became separated by more and more incoherent raving. Finally:

As part of [the Emperor Julian's] personal quest for authorization, he tried to rehabiliate Delphi in AD 363, three years after it had been ransacked by Constantine. Through his remaining priestess, Apollo prophecied that he would never prophesy again. And the prophecy came true.

if [American Indians, or Zulus, or Greenland Inuit, or Polynesians, or any other human group presumably isolated from second-millennium-BC Assyrians] were perfectly normal conscious people like us, then Jaynes is wrong about everything.